19 December 2006

Happy Hanukkah to all!

Friends of ours have a darling baby girl just over a year old who's undergoing surgery in Philadelphia while her 3 older siblings stay here in the DC area with loving family. They are devout Catholics; friends and family have been sending messages of love, support, and prayer on their CarePage. Part of mine from Friday afternoon:

Love, Faith, and Light

You are surrounded by the loving thoughts and prayers of so many of us who cannot be with you in person. I draw inspiration from what others have written, and say with them: "May God's love surround you and you see miracles in the upcoming days."

Tonight will be the first night of Hanukkah. The candles shine as a light of hope against the darkness, little by little, increasing each night until the menorah is ablaze with light. When we light the candles, we say: "Praised are You, Lord our God, Ruler of time and space, who accomplished miracles for our ancestors in ancient days, and in our time." There are miracles small and great every day--your love for each other; your lovely children. May we continue to know the miracles done in our time for us, and may your daughter have a good surgery and a speedy recovery.

Hanukkah is a holiday of prevailing against the odds, of seeking and finding strength in faith. Tomorrow in synagogue one of the readings comes from the prophet Zechariah, which couples his vision of the menorah with these words: "Not by might and not by power, but by My spirit, says the Lord of Hosts." May you be sustained by God's spirit, and by the love that we all have for you and for Gabbi. The Psalmist says, "In Your light we see light" (Psalm 36:9); in the light of the love of family and friends for you, we see God's light.

"Hope in the Lord and be strong; Take courage, and hope in the Lord." (Psalm 27)

On the commonalities in observance of the "holiday season," various as those holidays are:

Everyone could use a little more light in a dark time--all of these mid-winter holidays are about trying to increase the light against the darkness: from the menorah to Advent candles and Santa Lucia's blazing crown of candles (her day is my birthday!) to the Kwanzaa kinara, lighting candles often serves as the symbolic expression of this wish. The more the merrier, say I!

Gals and Geshem gets the greenlight!

The proposal to adopt the egalitarian version of the Geshem prayer found in the Masorti Siddur Va'ani Tefilati (distributed with the agenda) during Musaf of Shemini Atzeret was passed in a unanimous vote. Copies of the prayer in Hebrew with an English translation will be distributed during the service. It was suggested that the leyning coordinator should provide a copy of the prayer to the person leading Musaf.

29 November 2006

When in Rome...

"Didn't we just read in last week's Torah reading, 'There shall be one law for you, both for the stranger and for the native citizen'?" They were unmoved, but I was beginning to cry. So we left, and rejoined the rest of my family sightseeing in Milan's cathedral on a Shabbat morning, instead of in synagogue.

Luckily, that was the only time in our visits to synagogues abroad (Israel, Greece, England) and in the U.S. as a mixed couple that we were not made welcome as a couple because one of us was not Jewish. But that one casual rejection cut deeply: I'm glad we didn't have to endure it in a place where we're looking for community, and I feel for those who do. And I thank all those in my Jewish community in Arlington, VA (at what is Congregation Etz Chayim) for looking at my non-Jewish father, Jewish mother, and us 3 kids and seeing a family who's part of their community--not an outsider, a transgressor, and 3 future "victims" of assimilation whose Judaism will never stick.

I'm not going anywhere. :)

But I'm also not going to reject or abandon the non-Jewish members of my family and my husband's family, or parts of our past experiences that have to do with non-Jewish religion, in order to be where I am or go where I'm headed.

01 November 2006

More on tallit, tefillin, etc...

With an anecdote, and a promise to say more soon (I first wore a tallit & kippah at my youngest brother's bar mitzvah, Parshat Vayera in 1991, and am going to give a dvar torah for that parshah in 2 weeks that deals with women & time-bound mitzvot[TBM]/ritual garb).

I just came back from the USCJ Seaboard Region Biennial Convention--which was happenening at the same time as Youth Director/USY and Kadima (youth group) staff training, so all of us enjoyed spirited davening & Shabbat meals together. I was the youngest among the non-Youth Director types (I'm 32, the next-youngest was a 42-yr-old woman who's president of her congregation; one or 2 of the Youth Directors looked to be older than me), who generally ranged from mid-50s/60s up to near 90.

I noticed on Friday night that the convention women were ALMOST ALL wearing kippot (sometimes girly ones, wire with beads, etc--but definitely kippot, not doilies, and only a hat or 2 to be seen--one on the 90-year-old--sometimes for fashion & with some other kippah etc underneath), and none of the younger women (20s & 30s) except me were doing so. On Saturday morning a glorious array of beautiful tallitot were to be seen, not just on the women (though we have the best ones!) but also on the men--and not only were ALMOST ALL of the convention women (and our honored speaker/scholar-in-residence, Rabbi Naomi Levy) wearing tallitot, but I'd say the #s of non-tallit-wearers were almost equal among the men and the women: there were a few guys not wearing tallit (not their custom before marriage? left theirs at home & there weren't extras brought? don't always wear one & didn't feel strongly about it? I don't know!) and a few women not wearing tallit.

Among the youth director/advisor contingent, only 2 women were wearing tallit + kippah: one who looked to be in her mid-40s, and one younger woman (who had not been wearing a kippah Friday night); there were also a few guys in that contingent not wearing tallit, but the ratio was nowhere near the same. I was pretty fascinated by this difference between the age groups/contingents, and had some guesses about some reasons that might account for it...but I was interested in talking with the older women about why they wore tallit/kippah (and when/why they started) and to the younger women about why they didn't.

So, after having some nice conversations with the older women on the former point, I took the opportunity at a meal on Sunday to ask the regional youth director (who headed up that part of the program & had moderated a panel I was on that morning, and had led some of the davening on Shabbat) about what I'd noticed --

and she burst out: "You're the THIRD person who's asked me about it!!!! I don't wear a tallit & kippah & tefillin & I'm proud of it!!!!"

(later said it's not that she's proud of it or making a statement, it's just not the way she grew up & so she's not comfortable doing it, but she also thinks that for younger women who have always known it's an option it's not as big a deal as for these older women who are reclaiming something in Judaism that had always been denied them as forbidden to women)

But I just wanted to highlight the switcheroo there: she felt pressure because she was being asked by others "why aren't you doing these things?" (i.e., this is the norm for our crowd: involved egalitarian Conservative Jews who are women) rather than, as many of us have been asked in other contexts, "why are you doing these things?" (i.e., this is not the norm for involved/observant Jews who are women).

One person was asking her with a critical agenda, but I think others of us were just curious (though I would hope to persuade her to try wearing tallit--I'll certainly send her my dvar torah when it's done). But she got the message that the rest of us don't take it for granted that not being TBM-obligated is the norm (or that you can recognize yourself as TBM-obligated but particularly neglect the ones that have been or seemed traditionally male).

Similarly, when daveners (men or women, and it IS women as often as men!) choose to daven the amidah option without the matriarchs (since our siddur, the revised Sim Shalom ["Slim Shalom"], gives both options), I ask them why they don't. Their assumption often is that the default is without matriarchs--often, it has been for them, and so they're "not comfortable" or "haven't practiced" adding them (they don't usually have an ideological/halakhic reason, though they certainly could)--whereas in our community, it really is becoming (if it hasn't already become) the norm to include them, so that the dominant question becomes "why are you omitting the imahot?" (or, more neutrally "not using the names of the imahot":"not adding them" tips the rhetorical balance the other way) rather than "why am I including/adding them?"

Tefillin trials and triumphs

I laid tefillin for the very first time today. M. and I got to services sometime in Birkhot HaShachar [the morning blessings--pretty early on but not the very first thing], and he took out his tefillin, and I took out "mine" (my brother's: he lives in Singapore, and the last time we were home in Louisville, where his tefillin have been languishing unused, I asked if I could take them to DC and borrow them for now--he said sure). I watched what he did, followed his lead on the shel yad [the one for the hand], listened for his whispered instructions when I wasn't sure; I discovered that my brother's tefillin shel rosh [the one that goes on your head] was way way way too big in circumference, and I didn't know how to make it tighter on the spot (didn't seem like a slip knot--needs un-and re-tying?), so I just settled for trying to tuck the back of it under my hair and keep the whole thing from slipping down onto the top of my glasses. I had just finished up the shel yad, got my nice letter-shin shape on the back of the hand, was figuring out how to tuck the last end bit under the wrapped sections on the palm side and feeling pretty pleased, looking forward to saying a shecheyanu for this new experience....

When A Man In A Position of Clerical Authority came up to burst my bubble. "You've got it on wrong. It's a slip knot--you need to go against the slip knot" (re: the shel yad, which I'd done as M. did it.) "And this is too loose" (re: the shel rosh; "I know," I said, "It's not mine and I haven't done this before, which you can probably tell.") So I took it off, reversed it (and so did M., even thought I think he'd probably been doing his wrapping however he's done it for the past X years, even if he hadn't done it recently?), and rewrapped down to the hand, only to be told, "You don't have it wrapped 7 times" (I didn't realize that doing one above the elbow didn't count) and "It's going to slip, because you didn't wrap it straight, and it's not tight" (actually, it didn't slip, and it was tight enough to be uncomfortable-ish and make me feel like my left arm was quasi-immobilized all through services: I figured if it wasn't turning red or purlple, though, I was probably okay). He took the straps and did the wrapping of the hand for me--"see, you want it to be loose over the finger"--doing a serviceable but much less aesthetically pleasing job leaving me a rather middle-heavy raggedy letter-shin shape on the back of the hand. I finished it up, and then went over to ask him in a whisper whether there was anything I could do to tighten the shel rosh: could he help me? "I can't deal with that right now," was the reply.

I was glad to be laying tefillin, but it wasn't much of a fun experience. It's a good thing I have a thick skin (only figuratively: my literal skin is quite thin & subject to bruising, probably more so than my ego etc.), but this was not a first-tefillin-laying that's likely to encourage anyone, especially women (why are you doing this? you've never even handled these before: what makes you think you have any clue?), lay tefillin. I don't recall whether any other women there besides the ones who are ordained clergy of one sort or another were wearing tefillin there this morning: I think not.

-------------------------

Since the time that I wrote the above, I have layed tefillin 2 more times. Each time has gotten better. I'll keep going!

And for anyone who missed Tefillin Barbie, you really do need to check her out. (There's still time to make a bid in her eBay auction!)

Joy and Its Opposite(s)

As a consequence, I haven't blogged things I'd like to. So I guess for now what I can do is offer bits & bobs of things I've been saying, but meant or wanted to say more eloquently. And may someday.

But the best is the enemy of the good. And done is better than not done. So here's something I wrote on a friend's blog, in response to his post on Joy

[I begin by quoting a piece of his post]:

this goddamn soul-crushing American fear of wasted time—the relentless drive to be productive at every moment of the day. Not to oversleep. Not to take a vacation that is longer than ten days, lest your life fall apart completely in your absence.

Two thoughts, one negative, one postitive:

1) When I read this section of your post, I thought immediately of what Auden diagnosed in us moderns--what I recognized all too well in myself on first reading it--in "In Praise of Limestone":

Not to lose time, not to get caught,

Not to be left behind, not, please! to resemble

The beasts who repeat themselves, or a thing like water

Or stone whose conduct can be predicted, these

Are our common prayer, whose greatest comfort is music

Which can be made anywhere, is invisible,

And does not smell.

But I also take comfort in his solution/offer of another perspective:

In so far as we have to look forward

To death as a fact, no doubt we are right: But if

Sins can be forgiven, if bodies rise from the dead,

These modifications of matter into

Innocent athletes and gesticulating fountains,

Made solely for pleasure, make a further point:

The blessed will not care what angle they are regarded from,

Having nothing to hide. Dear, I know nothing of

Either, but when I try to imagine a faultless love

Or the life to come, what I hear is the murmur

Of underground streams, what I see is a limestone landscape.

2) And yet, there is a positive version of the desire to make each moment productive--not unreflectively productive of more Gross National Product, but of whatever it is that one most truly values. Love. Joy. Freedom. Choice. Beauty. It can come at too high a cost--and many devotees of Pater's gem-like flame could use some of Auden's relaxed approach--but I have always been drawn to his appeal to make each moment a significant one:

Every moment some form grows perfect in hand or face; some tone on the hills or the sea is choicer than the rest; some mood of passion or insight or intellectual excitement is irresistibly real and attractive to us, -- for that moment only. Not the fruit of experience, but experience itself, is the end. A counted number of pulses only is given to us of a variegated, dramatic life. How may we see in them all that is to seen in them by the finest senses? How shall we pass most swiftly from point to point, and be present always at the focus where the greatest number of vital forces unite in their purest energy?

To burn always with this hard, gemlike flame, to maintain this ecstasy, is success in life. In a sense it might even be said that our failure is to form habits: for, after all, habit is relative to a stereotyped world.... Not to discriminate every moment some passionate attitude in those about us, and in the very brilliancy of their gifts some tragic dividing of forces on their ways, is, on this short day of frost and sun, to sleep before evening. (Conclusion to The Renaissance: online at http://www.victorianweb.org/authors/pater/renaissance/conclusion.html)

On another note, I find this simple language of the natural world almost unbearably poignant:

on this short day of frost and sun, to sleep before evening

or, from the Biblical prophetic writings (Jeremiah 2:2; loose translation):

you followed after me in the wilderness, in a land unsown

I've often felt that I don't know what to do, scarcely know who to be, or how I am to make my way in this world.

But as long as there are such words, such feelings, in it...I'll be all right, we'll be all right.

Each mortal thing does one thing and the same:

Deals out that being indoors each one dwells;

Selves -- goes itself; myself it speaks and spells,

Crying Whát I do is me: for that I came.

(I love Hopkins so much...poor God-wracked GMH, crying so often not What I do is me but rather, out of those depths the psalmist knew as well, the mind, mind has mountains; cliffs of fall / Frightful, sheer, no-man-fathomed...)

And yet another way of seeing it, from the chassidic tradition:

Reb Zusya said: In the world to come, I shall not be asked, "Why were you not Moses?" I shall be asked, "Why were you not Zusya?"

I know I'm not Moses, or Elizabeth Bishop, or Helen Vendler, or Abraham Joshua Heschel...

I may not be sure of what it means to be Rebecca B. (and I've had different conceptions of the matter over time) -- but I do have some sense...and I owe it to myself and to others to try to find out...

rather than to try to remake myself in some ready-made, readily-approved form -- a doll, or series of dolls, plastic but not pliable: Successful Lawyer Barbie, Star Professor Barbie, Mother of Precocious Darlings Barbie, Big-Shot Mover and Shaker Barbie...

Hold fast to that joy. And to the search for it. And to what it makes you. Hold on.

Hazak hazak v'nithazek: let us be strong and let us strengthen each other.

09 October 2006

Gals and Geshem take two

Be sure to check out the versions available online, linked to in Zack's original post:

- "Geshem: Verses for our mothers" by Mark Frydenberg;

- an egalitarian version of Geshem by Rabbi Yoram Mazor of the Movement for Progressive Judaism in Israel (which ZShB praised as "closer in poetic spirit to the original")

Happy Sukkot (and/or Ramadan, full harvest moon, belated Feast of Saint Francis, etc.) to all!

Edit:

okay, this is a very not-clever way of doing things, but here's a JPEG of the text by Rabbi Dr. Gil Nativ, from the aforementioned Israeli Masorti siddur Va'ani Tefilati. Apologies for the bad orientation: I'm still not sure how to do much with things I scan, etc. -- but at least this way you can save it on your computer, manipulate it to face the correct way, etc. [RB note: I now have an English translation for this Hebrew--which has now been officially accepted for use in my minyan; please see the end of this post!*]

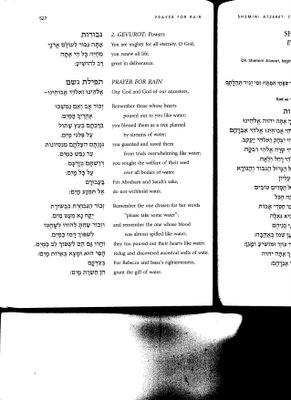

...and here's a JPEG of the version from Siddur Eit Ratzon (it cuts off the transliteration column, but it's got the complete Hebrew text & English translation; you can contact me if you want a PDF or JPEG of the cut-off page area; it says that it is based on the text by Mark Frydenberg):

and finally, the version from the attractively-laid out interlinear Siddur Hadesh Yameinu (from Congregation Dorshei Emet, the Reconstructionist Synagogue of Montreal; I do not know the attribution for its newly-composed elements & would welcome more information to give cresit where it is due!)):

And here's an English composition I've just been made aware of:

A congregant of mine created her own English egalitarian additions to the tefilat Geshem. I forward them for those who might be interested, with her permission.

-- Josh Hammerman

TEFILLAT GESHEM – THE MISSING VERSES

By: Karen Hayworth Hainbach

REMEMBER SARAH

Lively, lovely eyes, clear as aqua water

Amid two harems, she stayed pure as water

She greeted passers-by with food and water

Her laughter bubbled as a spring of water

Congregation: For Sarah’s sake, send water!

REMEMBER RIVKA

She kindly sated man and beast with water

Guided by faith elemental as water,

She transposed twins, at odds as oil and water,

Switching Isaac’s blessing, precious as water

Congregation: For Rivka’s sake, bless us with water!

REMEMBER LEAH

Spurned, soft eyes burned by tears like salty water,

Sustained by faith deep as a well of water,

Fertile as a field, surfeited with water,

She praised God, thanks overflowing like water

Congregation: For Leah’s sake, favor us with water!

REMEMBER RACHEL

She met her husband by a well of water

He yearned for her as sabras thirst for water

Her children exiled to Babylon’s water,

Her tears cascaded as a fall of water

Congregation: For Rachel’s sake, comfort us with water!

REMEMBER MIRYAM

Miryam the Prophet, named for bitter water,

Protected Moses’ basket in the water

Timbrel in hand, she danced beside the water

In her merit, you sent the well of water

Congregation: For Miryam’s sake, provide us with water!

REMEMBER THE DAUGHTERS OF ISRAEL

They shunned the Calf - their virtue shone like water;

Gave copper mirrors, reflective as water,

To fashion the Mishkan’s laver of water;

And monthly dunked in mikvas’ cleansing water

Congregation: For their sake, shower us with water!

November 2004

* Thanks for Rabbi Leonard Berkowitz for providing me with this translation:

Geshem Prayer

for Rain

From Masorti Siddur Va'ani Tefillati, 1998

additional verses by Rabbi Gil Nativ

Translation: Rabbi Robert Scheinberg

Our God and God of our ancestors:

a Remember our father (AV), whose heart poured out to You like water;

b You blessed (BERACHTO) him, as a tree planted near water;

g He and his beloved drew near (GIYER) all who were thirsty for water;

d At age ninety, from her breasts (DADIM) milk flowed like water;

For the sake of Abraham and Sarah, do not withhold water!

h Remember the one (HANOLAD) whose birth was foretold as the angels drank water;

v You instructed (VESACHTA)

his father to spill his blood like water;

z The meritorious one (ZAKAH) gave the father's servant to drink from a pitcher of water;

h She hurried (CHASHAH) to draw also for his camels from the well of water;

For the sake of Isaac and Rebekah, grant the gift of water!

t Remember the one who took (TA'AN) his staff and crossed the Jordan's water;

y He gathered his heart (YICHED) and rolled the stone from the well of water;

k A bride (KALAH) switched with her elder, whose eyes were like water;

l She was not (LO) comforted over her sons; her tears were like water;

For the sake of Jacob, Rachel, and Leah, do not withhold water!

n Remember the one drawn forth (MASUI) in a bulrush basket from the water;

n They said (NAMU), "He drew water and provided the sheep with water."

s On the Sea of Reeds (SUF), he heard his sister lead a song at the water;

a In the desert there arose (ALTAH) on her behalf a well of water.

For the sake of Moses and Miriam, grant the gift of water!

p Remember the one appointed (PAKID) over the Temple, who would immerse himself five

times in water;

t He went (TZO'EH) to cleanse his hands with the sanctification of water;

q The poor one called (KAR'AH) out Your name; her love for You could not be

extinguished by water;

r You accepted (RATZITA) her returnees from the land of rivers of water.

For the sake of Zion and her Temple, do not withhold water!

sh Remember the twelve (SHNEMASAR)

tribes of Israel, whom You brought through the

water;

sh You sweetened (SHEHIMTAKTA)

the brackish marsh for their sake into sweet water.

t For You their descendants' (TOLDOTAM) blood was spilled like water.

t Turn to us (TEFEN) for

our souls are engulfed like water!

For all of Israel's sake, grant the gift of water!

For you are Adonai our God

who causes the wind to blow and the rain to fall

For blessing and not for curse (Amen)

For life and not for death (Amen)

For abundance and not for scarcity (Amen)06 October 2006

05 October 2006

Machzor Madness: In with the New!

I davened out for the first time out of Machzor Hadash/The New Machzor these Yamim Nora'im, at both the shul where I belong & the shul where I work--and I much prefer it to either the Harlow (which my previous Conservative kehillot have used, and which I led Rosh Hashanah/YK davening out of at Yale for several years) or the old Silverman (which the Traditional Minyan at Adas still uses, and which my childhood shul used lo those many moons ago).

It's got all of the advantages of the Harlow:

- Conservative, not Orthodox, in its texts

- not outrageouly voluminous and stuffed with piyyutim no one knows, but

- keeps enough of the traditional texts and piyyutim people do know!

- provides an alternative Yom Kippur mincha reading from Lev. 19 as well as the traditional reading of Lev. 18

- no evil purple text for Shabbat insertions (and is more attractively & legibly laid out in general)

- actually translates on the left what's there in the Hebrew on the right, instead of abridging or fudging it (drove me crazy the way Harlow splits up the passages in Rosh Hashanah musaf amidah translation so you can't actually use it to see what you're davening when you know most but not all of the unfamiliar vocabulary), which allows you to actually use the 2 simultaneously or back-and-forth, unlike Harlow's set-up which presumes either complete Hebrew literacy or total ignorance of the Hebrew side of the page

- has in the back an "alternative Amidah opening" which includes the matriarchs, and includes them all in its English translations of the Amidah (with a note saying that the translation is based on the alternative opening found on page 800-whatever)

- has gender-sensitive language (I forget whether they claim to be gender-neutral, gender-balanced, or gender-sensitive...but I do know there's not a bunch of referring to God as He all over the place; I believe they pull the same trick as Slim Shalom re: phrases like "Adonai" or "Avinu Malkeinu," of transliterating them in italics in the English rather than either translating them with the gendered terms "Lord" and "Our father, our king" or with somewhat less accurate and less specific gender-neutral terms such as "Sovereign" and "Our parent, our ruler")

- has good interpretive selections, separate from the translations (which, as I've said above, actually are translations of the Hebrew, instead of giving us a new English version of the Ashamnu that concludes "we are xenophobic, we yield to evil, we are zealots for bad causes"), and more of them as little short thought-provoking observations at the bottom of a page, thematically linked to the main traditional text appearing above it

- has a martyrology that doesn't make me wince, but does make me cry--one that acknowledges that the history of Jewish suffering didn't just skip from Roman oppression to 19th/20th-c. Eastern Europe and Nazi Germany with nothing in between and nothing after (even if the rabbi leading Musaf in my service didn't use any of the 3 passages that had to do with medieval massacres and forced conversions, they were in there: one had to do with the Jews burned in the marketplace of Blois in the 12th century--a Jew from Sens drove me there at 11 at night, back in 1994, because I had wanted to visit the site) -- plus it acknowledges and includes Yiddish, the language spoken by most of the Jews who died in the Holocaust (prints the Yiddish text as well as the English translation of the Partisans' Song), instead of continuing to ignore the vernacular of the vast majority of Ashkenazi Jews from medieval times until the early-to-mid-20th century in favor of liturgical & modern Israeli Hebrew on the one hand and late-20th-c. English on the other

- and that doesn't commit the transgression that I regard as politically charged and theologically near-blasphemous, of asking me to recite an Al Khet for "the sins which we have sinned before you and before them"--the six million--by evils such as appeasement or failure to act. We don't have intermediaries, saints, or intercessors in Judaism (by and large), and I'm not about to set up the victims of Nazi genocide, no matter how great their suffering or how important in our Jewish history, as some kind of semi-divine body before whom I should be genuflecting and confessing my sins, particularly ones of a semi-political nature.

- has fewer hokey moments in the English translations or interpretive selections that would make me roll my eyes rather than raise them in reflection or gratitiude (I don't miss not having "who shall be torn by the wild beast of resentment, and who shall be drowned by the waters of jealousy"--I don't mind the idea, but never liked the execution, and I really do want to keep actual translation & interpretation separate)

- The Avodah service does not include all of the descriptive text in the Hebrew (which we always skipped at Yale anyway: the rabbi read the narrative framing in English regardless): it provides the English for this narrative framing and then both Hebrew & English for everything the Kohen and the people said & the description of the recitation of the Name (which was what the hazzan would read/enact in Hebrew at Yale anyway). Fine by me! And if people really wanted more, it would be easy to make booklets/photocopies.

- I don't remember seeing some of my old favorites from the English selections in the Harlow (poems by Anthony Hecht and maybe also A.M. Klein?)...but so much is gained in the other English readings they add that I can deal with this potential loss.

B'shalom,

Becca

[shamelessly repeated from my post to the Shefa Network

group ]

Oh, and P.S.:

27 September 2006

More of my Jewish blogging

http://annabel__lee.blogspot.com/2006/09/always-and-never.html

and hope to update links here for the many orphaned posts I have wandering around the blogosphere...but not tonight...oh, ok just a few...

Guilty Pleasures:

my religion-related posts on a non-specifically-religion-related board include:

- on "religious" vs. "spiritual," kashrut, & more

- initial post on "religious," "spiritual," "frum" etc.

- what God does & doesn't do to "put us in our right place"

- Jewish: religious affilation? ethnicity? and matri/patrilineality

- Proselytizing & conversion to Judaism

- Golden Rule/loving your neighbor as yourself, as conveyed by various religious traditions

- Female religious leaders in Islam

- Religious texts/icons and public buildings/symbols (incl. Ten Commandments)

- Religion/faith and logic/questioning

Intermarriage 101

I'm happy to talk about the whole Jews-and-non-Jews part of my/our experience, since:

--I grew up in a household where Judaism was the only religion practiced, but my father is not Jewish & has never converted;

--my now-husband & I were a couple for 7 years before he ever thought about conversion

--we have lots of friends (including many members of our Jewish community back in New Haven) in couples where one partner was not born Jewish [some have become Jewish--not necessarily before marriage; others have not converted]

--we had lots of non-Jewish and not-traditionally-observant Jewish friends & family at our wedding for whom the structure, language, & rituals of the wedding would be unfamiliar (so we put together an explanatory sheet & had explanations in the wedding program...everyone had a great time & thoroughly enjoyed it, especially the music & dancing!)

Some URLs of interest may be:

http://www.joi.org/ -- Jewish Outreach Institute

http://www.interfaithfamily.com --

which also has a link to a new blog "about a young Jewish woman's relationship with her non-Jewish atheist boyfriend in InterfaithFamily.com's new blog, Peace Within These Walls" (the person writing it grew up in the Maryland burbs here!)

Both have all kinds of good resource pages, links, bulletin/discussion boards, as well as blogs etc.

I've commented pretty often on the JOI blog and on the 2 blogposts at the site above (you can click on the comments at http://blog01.kintera.com

I approve of my friend Zack's piece at http://zackarysholemberger

and there are some other comments of mine on it/these issues at

http://zackarysholemberger

(Funny sidenote: I guess I've commented enough about it at places that people read that when I Google "intermarriage + Becca"

all of the 1st 4 hits are by or referring to me--2 JOI comments, 2 mentions on Zack's blog...)

I also got involved in a long discussion on the Shefa Network listserv (something you might be interested in) about intermarried family issues--they're handily linked to on their webpage here:

http://www.shefanetwork.org

You're welcome to borrow any books I have--not just on weddings/marriage/interfaith issues, of course! Feel free to come browse my shelves sometime, or ask if I have a particular book you're looking for. :)

No frontiers to our hope

I am honored and pleased that she said yes.

Rosh Hashanah 5767

Immigrants into the New Year

Rabbi Lisa Grushcow, Congregation Rodeph Sholom

In 1939, a Viennese Jewish man enters a travel agent's office and says, "I want to buy a steamship ticket."

"Where to?" the clerk asks.

"Let me look at your globe, please."

The man starts examining the globe. Every time he suggests a country, the clerk raises an objection. "This one requires a visa. This one is not admitting any more Jews. The waiting list to get into that one is ten years."

Finally the Jewish man looks up. "Pardon me," he says, "do you have another globe?"

Out of that question, the state of Israel was born. Not another globe, but another country. It is for this reason that Israel is a country of immigrants, welcoming Jews from across the globe. It is for this reason that Israel itself is an immigrant country, creating not just a home for Jews but a Jewish home. It is for this reason that its anthem is called Hatikvah, 'the hope'. Israel holds the hope of making the desert bloom, yes; of a democracy and peace in the Middle East, yes; but for most of the people who go there, it holds the hope of home. Russians coming from the chaos of the Former Soviet Union. Ethiopians fleeing famine. And yes, Americans, looking for an extraordinary place in which to live ordinary lives.

It is that hope which was jeopardized this summer, in the conflict with Hizbollah. As with the intifadas before, the war this summer raised a grim possibility: that Jews are safer out of Israel than inside it. That the hope of making a home there, of living a life there, is misplaced.

We experienced something similar nineteen hundred years ago. In the second century, the Jews who lived in the Land of Israel faced persecution by the Romans. Rabbi Nathan, a rabbi from that time, asks what God means by the phrase "those who love Me." He then goes on to explain:

…[this] refers to those Jews who live in the Land of Israel, and in consequence put their lives in jeopardy when they keep the commandments. "Ma lekha yotzei lehareg? Al she-malti et b'ni". Ask a Jew in the Land of Israel why he may be killed tomorrow, and he will tell you, `for nothing more than circumcising my son'. "Ma lekha yotzei lisaref? Al she-karati ba-Torah". Ask him why he may be burnt up tomorrow, and he will tell you, `for nothing more than reading a book of Torah'. " Ma lekha yotzei litzalev? Al she-akhalti et ha-Matzah". Ask him why he may be crucified tomorrow, and he will tell you that it is for nothing more than eating Matzah. [ source: Mekhilta deRabbi Ishmael, Beshallach.]

In other words, these Jews were not doing anything extraordinary beyond trying to live ordinary lives – in the land of Israel, and as Jews. Rabbi Gordon Tucker has written his own midrash based on this one, following the events of this summer. Asking who these Jews are now, he writes:

"One of them could be an Argentinian Oleh going to a Bar Mitzvah in a bomb shelter in Kiryat Bialik, who, if he didn't quite get to the shelter in time, would be in danger of being consumed by a rocket's fireball. 'Why might you be burnt tomorrow? For nothing more than wanting to be present for the reading of the Torah.' Or she could be an American immigrant who works as a nurse at the hospital in Nahariya. 'Why might you be killed tomorrow? For nothing more than going to work to tend the sick.' Or, it could be a Moroccan family from Kiryat Shemoneh doing whatever we do when we are just at home. 'Why might you be shot tomorrow? For nothing more than staying in our home in the Land of Israel.'" [source: Rabbi Gordon Tucker, Temple Israel of White Plains, Rosh Hashanah 5767 (shared at the New York Board of Rabbis sermon seminar, September 5th, 2006). I am indebted to Rabbi Tucker for bringing the Mekhilta text to my attention.]

It is no accident that all these examples are of Jews who have made aliyah. There is something extraordinary about all of these Jews, who have come from the four corners of the earth to make a better life in Israel, for themselves and for their people. There is something extraordinary about the fact that the largest single immigration from Jews in the West came to Israel just this summer, in the midst of the war with Hizbollah. On August 16th, the largest group of immigrants in the history of Israel came from North America and Europe, undeterred in their desire to make Israel their home. That is no less than extraordinary. And there is something extraordinary about each and every one of Rodeph's Sholom seventeen teenagers who went to Israel this summer – not to mention their parents, who did not put them on the first flight back to New York when that first Katushya hit.

Many of those teenagers were taking part in the Reform movement's summer teen experience. The program starts not in Israel but in Prague, and from Europe, they take a boat to Israel; even our tourists are immigrants. The teens re-enact the 1947 voyage of the Exodus, which carried a boatload of Jewish refugees from the death camps of Europe to Israel's shores. The catch, of course, is that Israel was not yet Israel; it was ruled by the British, and so, unlike the Argentinian and American and Moroccan olim, immigrants, of the past half century, these European refugees were illegal immigrants, law-breakers who had to be stopped. The British rammed the boat when it got near Haifa, and in the fighting that ensued, one Jewish mother said, "I'm going to stay alive so my child won't be burned in a gas chamber. I'm going to live in decency without being afraid. There are no frontiers to Jewish hope." [source: Ruth Gruber, Exodus.]

There are no frontiers to Jewish hope. 'Od lo avda tikvateinu', say the words of Hatikvah, our hope is not yet lost: to be a free people in our land. Look in your high holiday bags for information about our Israel Emergency Fund, and the projects we are asking you to support. If Jews can keep streaming into Israel looking for a better life, it is incumbent on us to help them find it.

There are no frontiers to Jewish hope. It is not hard to be sympathetic to that mother holding a baby in her arms, demanding to live in decency without being afraid. It is more painful for us to remember that refugees from the Holocaust pounded on Israel's doors because, as the story about the travel agent tells us, there was not much room on this globe. In Canada in those years, when a prominent politician was asked how many Jews the country could take, his response was: "None is too many." And here in America, quotas on Jewish immigration continued in full force during the war, and were not lifted until 1965. In the late 1930s, 83% of Americans were staunchly opposed to opening the country's gates to any more immigrants, never mind Jews. That woman on the Exodus was among the lucky ones; despite deportation of the the refugees back to Germany by the British, when Israel was established they could find a place to call home. Not so the refugees on the St. Louis, which left Hamburg for Havana in 1939. 937 Jewish refugees held visas for entry to Cuba, but that entry was refused. They tried to gain entry to the United States off Miami, and again they were refused. And so the St. Louis, with no other globe to choose from, was forced to return to Europe. Almost all of its passengers died during the war. God knows that is not a journey that we want to re-enact. [source: This statistic, and the background information on the St. Louis, is based on the on-line Holocaust Encyclopedia article, "The Voyage of the St. Louis," from the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum (http://www.ushmm.org/wlc

There were boats then, and there are boats now. Now the boats go from northern Africa to Southern Europe, from Cuba to America, from any place where people are desperate for a better life to any place they hope to find it. All these migrations are different of course. Two things, though, connect them all: all are illegal according to the laws of the time, and second, the hope for a life that is better than the life that has been left behind. There are no frontiers to human hope.

This summer, while the immigration debate was raging in the papers, I got my green card in the mail. My experience of the immigration process was, relatively speaking, a cakewalk. I had almost every advantage, except for that of a marriage recognized by the powers that be. But the process was empty of dignity, and with nary a mention of hope. I answered countless questions – am I a Communist, am I a terrorist, do I plan to become a polygamist – and underwent a battery of medical exams. Even with the help of a lawyer and with English as my first language, I found the process and the paperwork almost impossible to understand. At no point, though, was I told: this is a country of immigrants. You are part of a fine tradition. Welcome. And at every point, until I held that green card in my hand, I felt fear: fear that I might be separated from my family, fear that I might not be able to do travel to Israel with our day school's 8th grade, fear that my life, my home, everything I have built could be taken away in an instant. Receiving mail from the Department of Homeland Security will do that to a person.

The moment that stands out in my mind, though, was a cold February day. I had received notice to appear at the Bronx offices of the Immigration and Naturalization Services for my biometrics – fingerprinting and a photo. I was afraid that I would not be able to find the right building on the Grand Concourse, but I needn't have been concerned: I could see the place I was going from blocks away. It was the building with a long line of people snaking down the block. Each person clutched a piece of paper like my own, telling them when to appear; and each person stood, like I soon did myself, shivering outside in the bitter cold. Yet none of us would have stepped out of that line for an instant.

As I stood in that line, I thought of the immigrants before me in my family, how they come from Poland and Russia and the Ukraine; my Zaide, an orphan, who came not knowing a soul; and my Bubbe's father, who left a shtetl in Eastern Europe to become a fur trader in the Canadian north. Then I thought of the immigrants standing beside me in the line, people from all around the world, some carrying children, some leaning on canes in the cold. With all of them, I shared that basic hope: the hope of making a home. There are no frontiers to human hope.

It cannot be that there is such a divide between those of us with our official papers standing in that line, and those who come without papers, driven by the same dreams. Who am I to say that I would not do the same, in search of a better life for myself and those I love? I am not defending illegal immigration; it is one of the most complicated issues of policy in our times. I am not saying we should have no concern for the stability of our economy, the safety of our borders, or our national identity. I am asking that we have sympathy, even empathy, for the desperate desire to make a better life. I am asking that we treat those we encounter with dignity, and call on our government to do the same. I am asking that in the midst of all the policy, we remember that there are people on the line.

We do not need to look far to find support for this in our tradition. The words on the base of the Statue of Liberty are Jewish words: Emma Lazarus' "New Colossus," calling on us to extend our arms in welcome – "Give me your tired, your poor, your huddled masses yearning to breathe free." Thirty-six times, the Torah reminds us: we were strangers in the land of Egypt. And Abraham, whose journey we recall on Rosh Hashanah, is the paradigmatic immigrant, risking everything he has, leaving everything he knows, in pursuit of a dream.

When he is on the way to the akedah, to sacrifice Isaac his son, a midrash tells us that Abraham asks: What is to become of the promise? Has he made this whole journey only to lose that which he holds most dear? And God answers him by keeping Isaac alive. God answers him by insisting that his journey will continue, that all need not be lost. [source: Based on Genesis Rabbah 56:2.]

Abraham did not expect it to be easy, any more than the people who stood beside me in that line. A welcome mat need not be rolled out, but some sacrifices should not be asked. Migrants from Mexico should not be dying in the desert, trying to reach the border. Teenagers from China should not be in this country on their own, terrorized by the snakeheads who smuggled them here and threaten their families, too frightened to ask for help. Gay and lesbian families should not be torn asunder because their relationships are not recognized. Widows of restaurant workers who died on 9/11 should not be kept from visiting their families in their homelands, afraid that they could not return to the country where they lost the one they loved. There must be some other way. Until we find it, this country will keep missing opportunities, moral and economic alike. And until we find it, people will die.

In 1892, Anzia Yezierska, came as a Jewish immigrant from Eastern Europe to the United States. In her essay, "America and I," she writes:

…Great chances have come to me. But in my heart is always a deep sadness. I feel like a man who is sitting down to a secret table of plenty, while his near ones and dear ones are perishing before his eyes… all about me I see so many with my longings, my burning eagerness, to do and to be, wasting their days in drudgery they hate, merely to buy bread and pay rent. And America is losing all that richness of the soul.

The Americans of tomorrow, the America that is every day nearer to coming to be, will be too wise, too open-hearted, too friendly-handed, to let the least last-comer at their gates knock in vain with his gifts unwanted." [source: Anzia Yezierska, The Open Cage, p.33]

There are no frontiers to human hope. We have a lot for which to be grateful, as Jews in this country; we have reached a point where our gifts are received with open arms. But it was not always so. Not one of us sitting here can claim to have always been here. All of us either came here ourselves, or come from ancestors who immigrated so we could be born in this land, people who sacrificed so we could succeed. May we have what it takes to welcome others into the American dream.

Nostalgia connects us to the immigrant story, but all of us here are immigrants on this night/day. Rabbi Alan Lew teaches that that the journey is what these Days of Awe are all about:

"This is the journey the soul takes to transform itself and evolve, the journey from boredom and staleness – from deadness – to renewal… It is the journey from little mind to big mind, from confinement in the ego to a sense of ourselves as a part of something larger. It is the journey from isolation to a sense of our intimate connection to all being…. The journey home. This is the longest journey we will ever make, and we must complete it in that brief instant before the gates of heaven clang shut." [source: Alan Lew, This is Real and You are Completely Unprepared, p.8.]

And so the immigrant story is our story too, and we too dream a dream on this Rosh Hashanah. Certainly, some of us in this room are immigrants to this country, having uprooted ourselves to learn a new life. Some of us are immigrants to Judaism, brought here by determination and hunger and hope. But all of us are immigrants into the year to come. Each one of us is here, at the border of the New Year, hoping to make a better life. Each one of us is waiting to discover what 5767 will hold. None of us knows for sure. But we know that we need to leave the old year behind, and knock on the door of the new.

Some of you are coming from extraordinarily difficult years; others are coming from years overflowing with joy. All of us, though, are together on this night/day in that mixture of fear and hope – it reminds me of nothing more than standing together with other immigrants in that line, not knowing who would be let in and who would be sent back. Who shall live and who shall die, who shall be humbled and who exalted. We do not know, as we enter this new year, who will be standing here beside us when the next year comes. We do not know which marriages will be renewed and which will fall apart; which children will flourish and which will struggle; which jobs will be kept and which will be lost. All we know is that we are looking for the Promised Land; that we hunger for milk and honey; that we want the gates to be open to our pleas. But the story of Israel and the story of immigrants to these shores tell us nothing if they do not reflect Herzl's timeless words – im tirzu, ein zo agada – if you will it, it is no dream. Do we control everything that will happen in this year to come? Absolutely not. That's why on Yom Kippur we will say Kol Nidrei – even at the beginning of the year, we know there are promises we will not be able to keep. But it is in our hands to have the will, to dream the dream, to leave what we know and search for what we need.

There are those in this world that tell us not to try to move, not to try to change. Be happy with what you have; make the best of it; just make do. That is not the message of our history, and it is not the message of Rosh Hashanah.

Go back, some would say to the Israeli, leave the Middle East, give up on Herzl's dream. Go back, some would say to the immigrant, give up on making a better life, give up on finding a country where your children will breathe freedom like air. Go back, some would say to us all, go back to a broken relationship, a stifling job, thwarted dreams. I cannot believe this is what God wants. God wants us, like Abraham, to move. God wants us, like Abraham, to go to a land we do not know.

There is a woman in our congregation who is an immigrant to the United States from Mexico, an immigrant to Judaism, and, along with the rest of us, an immigrant into the new year. Her name is Cristina Ross, and in her conversion statement, she wrote:

"One of the meanings of the word 'Hebrew' is: 'dust raiser' because Abraham kept moving from land to land with his animals and clouds of dust would announce his presence. That is my personal wish for myself and the Jewish family I will raise… I wish for us to be Hebrews and raise dust wherever we go; we will announce who we are with pride, we will raise dust for social justice and the acceptance of the marginal, we will stir the passion of our community and we will wake up the world to peace and love. " [source: Cristina Ross, conversion statement, September 7th, 2006.]

No one can tell me we are not blessed to have such an immigrant among us, to remind us who we should be. As Cristina stated so beautifully, God wants us, like Abraham, to raise dust wherever we go. We stand here on the border of a new year, and we insist on a promised land. There is no other globe; only the one we inhabit. In Israel and in America, in this synagogue and in synagogues around the world, we enter the New Year and proclaim: There are no frontiers to our hope.